Evolution of the Nikolaj Camp

Uranium mining in the Jáchymov region was started by Nazi Germany in World War II and involved many prisoners of war. After the war, the mining efforts continued, but this time under supervision of the Soviets; the uranium was intended for the Soviet Union’s nuclear programme. Early on, the Soviets used the labour of thousands of German POWs. After 1948, the regime attempted to replace this workforce with civilian miners, but failed in its efforts; this proved problematic, because the primitive mining methods used by the Soviets combined with a low productivity required a significant increase in the number of workers. Already in 1949, the regime started deploying prisoners to the mines, and their numbers expanded very rapidly.[1] In 1949 alone, five prisoner labour camps were established in the Jáchymov region: Vykmanov, Mariánská, Eliáš, Rovnost and Svornost. Other camps followed. In 1954, there were in total 14,155 prisoners working in the uranium mines, accounting for 70–80% of the entire workforce.[2] It needs to be said, however, that not all of them were political prisoners; there were also criminal convicts and what were known as “retribution” prisoners, sentenced for collaboration with the Nazi occupation regime. Paradoxically, the latter two groups were considered less dangerous by the communists than political prisoners (who were often members of the social elite sentenced for acts that they did not commit) and enjoyed a relatively privileged position in the prisons and labour camps.

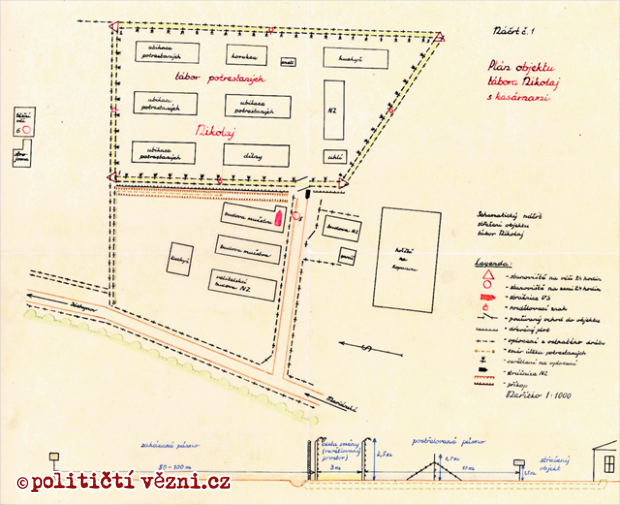

Forced Labour Camp (tábor nucené práce, TNP) Nikolaj was established on 1 September 1950.[3] Most people were sent to TNP camps without any trial, simply based on the decision of the Security Commission of a National Committee (“národní výbor”, a term used by the regime for regional authorities on various levels), and detained for a period of up to two years.[4] It was not necessary to prove that the person did anything wrong to send them to a TNP camp; the Commission could act on a simple suspicion that they were capable of an illegal act. The regime in these camps was only slightly better than in prison camps.[5]

The original Nikolaj Camp was disbanded on 15 February 1951. In autumn of the same year, Nikolaj was converted to a prison camp.[6] It became a large camp with a particularly brutal regime. Early on, the vast majority of prisoners were criminal convicts and retribution prisoners, many of whom were bullying the small group of political prisoners who accounted for about 10% of the camp’s population. The situation was most serious from May to August 1952 when political prisoners refused to accept new work performance standards and, with consent of the camp commander Ladislav Schamberger and political educator Jaroslav Kvapil (known as “Hnusák”, or “The Ugly One”), a “beating commando” of retribution and criminal prisoners was established under the leadership of Břetislav Janíček, a former Gestapo informer, with the aim to freely terrorise political prisoners. As Svatopluk Kráčmar wrote later: “These commandos forced their way into the barracks of political prisoners and brutally beat them until they lost consciousness or crucified them on the front sides of the bunk beds.”[7] The growing group of political prisoners however soon started fighting back. “Rudolf Pernický, who’s a general today, taught us the basics of self-defence: where to kick, where to punch and what to use as a weapon. We each found a piece of thick cable and never went to sleep without it… The beating eventually stopped, but hunger didn’t. In fact, it got worse.”[8] According to survivors, the conditions in the camp improved slightly after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Like the other camps, Nikolaj was characterised by inadequate housing conditions, minimal healthcare, constant hunger and very dangerous and hard work. We will never know exactly how many people were injured or died in this camp. In his research, historian František Bártík managed to identify 11 prisoners who died here (most of them as a consequence of injuries suffered in the mines).[9] The real figure, however, is undoubtedly higher than that. To illustrate the conditions in Nikolaj, let’s return to Svatopluk Kráčmar’s testimony: “There was always hunger in the prisons and camps. (…) In Nikolaj Camp, even potatoes were rationed. The camp commander (…) organised opulent dinners for his colleagues and superiors, all from food intended for the prisoners. They could even take the leftovers home. The prisoners were starving. They could get extra food from the civilian miners, doing some of the hardest work for them for a loaf of bread. If you did not meet your performance standard, you were sent back to the mines and had to keep working until you did, with no food and no rest. Repeat offenders were placed in solitary confinement.”[10]

In the second half of the 50s, mining in the Jáchymov region was winding down. The Nikolaj Camp was one of the last to be disbanded, on 30 June 1958.

[1] BURSÍK, Tomáš. Přišli jsme na svět proto, aby nás pronásledovali: trestanecké pracovní tábory při uranových dolech v letech 1949–1961. Prague: Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů, 2009. p. 44.

[2] BURSÍK, Tomáš. Přišli jsme na svět proto, aby nás pronásledovali: trestanecké pracovní tábory při uranových dolech v letech 1949-1961. Prague: Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů, 2009. p. 51.

[3] BÁRTÍK, František. Tábory nucené práce se zaměřením na tábory zřízené při uranových dolech v letech 1949–1951. Prague: Úřad dokumentace a vyšetřování zločinů komunismu PČR, 2009. p. 141.

[4] TNP camps of this type existed in Czechoslovakia from 1948 to 1954. According to the historian František Bártík, the total number of people incarcerated in such camps in this period was about 20,000. Other historians have provided much higher estimates.

[5] BÁRTÍK, František. Tábory nucené práce se zaměřením na tábory zřízené při uranových dolech v letech 1949–1951. Prague: Úřad dokumentace a vyšetřování zločinů komunismu PČR, 2009. p. 15.

[6] BURSÍK, Tomáš. Přišli jsme na svět proto, aby nás pronásledovali: trestanecké pracovní tábory při uranových dolech v letech 1949–1961. Prague: Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů, 2009. p. 47.

[7] Causa „Spravedlnost“. Historická penologie. 2005, (2). p. 17.

[8] LUKEŠ, Jan and PECKA, Karel. Hry doopravdy: rozhovor se spisovatelem Karlem Peckou. Litomyšl: Paseka, 1998. p. 85.

[9] BÁRTÍK, František. Zemřelé nesvobodné pracovní síly v oblastech produkce uranové rudy 1946 až 1986. Příbram: Hornické muzeum Příbram, 2011. p. 37.

[10] Causa „Spravedlnost“. Historická penologie. 2005, (2). p. 16.