Jozef Kycka

Interview with Jozef Kycka

"It is like if someone does something bad to you, you forgive, but you do not forget. That’s how I feel about Jáchymov." ~Mr. Jozef Kycka

Interviewer: Tomáš Bouška

This interview's English translation has been gratefully edited by Mr. Brian Belensky.

First I would like to ask you something about your childhood. When and where were you born?

I was born on February 23, 1928 in Opatová, Slovakiain the southern region of Levice. My father occasionally worked for farmers or for those people who owned land. I lived there until September 1928 when my whole family moved to the United States where my father found a job in a battery factory in Cleveland, Ohio. After about three years we returned together with my mom and older brother to settle some property disputes in Slovakia. They were resolved in 1937 and we were supposed to move back to the United States. I don't really remember things too well, but I do know there were two different shipping companies, Brehmen and Lloyd and one of them was facing bankruptcy. Another agent came to us and offered another company that we could travel with. Finally it took all too long and we couldn't travel through Hamburg anymore because it was 1938. We were then supposed to leave from Turkey, through the Suez Canal, around Africa, and then back to America. That all finally didn't happen so we stayed here. My brother joined the Slovakian Army[1] and was sent to a fast-proceeding division on the Eastern Front in Russia. While they were retreating he was separated from his unit and we got a statement that he had been killed, but I couldn't believe it. I attended the grammar school in Trnava because the Hungarians had occupied Levice. In our village there was one lady who was a nun in Trnava and she offered us to live in Trnava in the orphanage as boarders and go to school there. So we attended grammar school in Trnava until 1944, until the Slovak National Rebellion[2].

Do you remember the events of the Slovak National Rebellion and how the Soviet Army reacted?

It didn't happen close to us. Things happened so quickly on the night of August 28th. It was broadcasted on the radio and by August 29th the Germans had already occupied our country. We were liberated by the Soviet Army on December 20, 1944. We were occupied by the Soviet Army until the end of March 1945 until they finally retook Budapest. It was during those three months that we really learned about their brotherly love. It was the Second Army from Ukraine, which was led by Malinovsky and these people were mostly from Gulags[3]. We couldn't believe the things they were saying to us. They picked sixteen year-old boys to help them, including me. I shouldn't really say they choose us, but rather ordered us, "Tomorrow, you start." I had to go work in a bakery for three months. There were prisoners working with us and also soldiers who had a special insignia on their uniforms. This meant they were the elite guard. The main commander of this part of the front lived in our house. Every two weeks or once a month they held a trial. They always sentenced someone to death and executed them in our yard behind the water well. Once my grandma was going outside to throw out potato peels and she witnessed them shooting someone in the back of the neck.

Did you have the chance to talk to Gulag prisoners about their past?

These Cossacks told us some unbelievable stories. For example, one group was running around the labor camp and yelling that if they didn't meet the quotas, they should get death as a punishment. They were reporting themselves and asking for death. I didn't understand why. I told myself that it wasn't possible. There were many cases where a prisoner would tell you he didn't even know why he was there. When his neighbor would come into the Gulag and he would convince the first guy that he or his neighbor had informed against the first guy and so on. Then the next guy would come into the Gulag and say he had informed on the neighbor. I was always imagining that the Gulags or exile was something like exile during the era of the Tsar, but after hearing their stories I found out that these Gulags were liquidation camps where the whole families were separated. Wives were sent to one place, kids to another, and these people would live there in utter misery and starve to death. They even had to build their own dugouts and live in them. I don't know how they did this when it was 40 degrees below zero. We were not even able to imagine it. We suspected that they were only saying these things to get drink or wine because when they were sober they didn't want to talk about it at all. Only joining the army saved them.

Who exactly told you these stories?

These stories were told to us by Cossacks who were billeted in our house and worked with us in the bakery. In the bakery we helped to mix dough, make bread, deliver it, and so on. The bakers told us about it. There was a guy who told he was a priest and we thought he was a priest, but later when we understood Russian better we found out he was a prince, Sokolovsky. He was a Captain Second Class in the navy and from 1921 he had been in the Gulags in Siberia. He went through many Gulags and he said that his ability to bake saved his life. He would always bake some pastries for the commanders and would be saved. He was already sixty maybe sixty-seven. He was nearly deaf because a mine had exploded close to him or something similar to that.

All this happened before Communism started in 1948. Did you have any notion of what Communism meant?

I did because there was an old postman living nearby. He was a democrat and I used to visit him. We talked and he explained what democracy meant and gave me three books. These books were called "October Revolution" and they were written by Trotsky. They weren’t comedies or novels but chronological accounts, for example: Town Carycin, November 7th, 7pm or 8pm. A professor and his family were executed behind the town garages”; or “Leningrad, 8pm, from the bridge someone threw a doctor and his family into the Neva.” There were more stories like these that happened in other towns and at different hours. The officials who did these things were also described in the books.

You told me that your brother was reported missing and killed at the Russian Front. Did you find out later what happened to him?

After the war, my brother came home. He told us that when he had been captured near Odessa and had to march to Jekatěrinodar. When Svoboda decided to organize his own army, my brother decided to join it. He didn't talk about things much, but when we drank a bit he started to open up and told me about some horrible things.

What was Slovakia like after the war? Did you finish school?

After the war I went back to the gymnasium in Levice. I got into some trouble there. A friend of mine, Palán, broke his leg and we wanted to go visit him in the hospital. I didn't want to look disrespectful so I wore a tie and my friend Stano [in Slovak abbreviated nickname of the first name Standa] did as well. There were two other girls going with us. When we arrived at school, a professor came in and pointed his finger at Standa and I, hit us, and asked why we were dressed like that. We replied that we were going to visit our friend in the hospital, but he didn't believe us. He said, "It's March 14th[4] today and this used to be the Slovakian national holiday." He escorted us to the director's office and they called our parents to school. I was suspended from school because I had a "bad report" and I was forbidden to study at any high school in Czechoslovakia. I had to go to work in the heavy industry in Ostrava. Itas already in 1947 when they started to harass the democrats. I was in Ostrava during the February events[5]. The workers were given shotguns and stationed around the gates and important sites around town.

You didn't stay long in the north of Moravia did you?

No. I left because after that February when a friend of mine escaped across the border. He left a suitcase at my place telling me he was going to visit an uncle in Prague to see about a job. His uncle was a head doctor. My friend was caught trying to cross the border and was in prison in Cheb for two weeks. From there I got a letter with his apology for not telling me anything and for betraying me. He also promised he would explain everything after he was released. He never came back. He was released and he later escaped.

So he successfully crossed the border then?

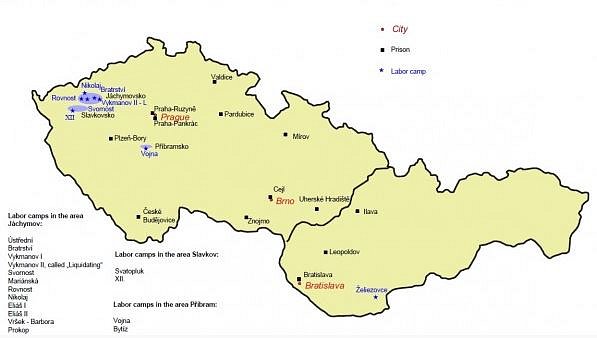

Yes. Policemen came to my boarding house a month later asking me where he was. I just told them that he was in Prague and that he left a suitcase at my place. I took the suitcase out and it was locked. They opened it and went through it. They took the suitcase with them and me along as well. When I was released I had to sign a paper promising that I wouldn't tell anyone about what happened or what they asked me about. At that time I noticed someone was following me. So I went home to Slovakia and my brother, who then worked at Jáchymov, was there by chance. The prisoners had started working in Jáchymov in 1945 or 1946 already. They recruited bachelors to be guards. So my brother told me, "Hey, come to Jáchymov. There are Russians and no one will be watching you there." So I went. In the fall or maybe in the end of summer in 1945, 60 Russian soldiers and their commander came to Jáchymov and guarded some of the camps. The names of the camps were Svornost (Concord), Rovnost (Equality), and Bratrství (Brotherhood). While they were there, they didn't let anyone else in except for those people who were supposed to work there. Then sometime in October they signed a mining agreement with the Soviets. So when I came to Jáchymov, I got a really great job from a lady named Pusíková in lab number 1. I worked with the high quality uranium ore. I measured the ore and did not much else. I arrived there in June 1948.

How was your and your brother's experience? You had to meet political prisoners there is that right?

There weren't many of them there yet. They started coming in 1949 and they practically took turns after the German prisoners. I was in Horní Slavkov when the prisoners also started coming. There were a couple of political prisoners among them, but they never talked about it. If you asked what they were sentenced for, you would typically get the answer that they were caught reading political magazines in someone's apartment. They were making fun of it and didn't want to talk more about it until they got to know you a little better. Then I met a couple boys from Slovakia. There was a guy named Kanys. There were more of them and they told me what was going on, what they were sentenced for, and how things looked. So I learned a little bit more with each conversation.

You were working in a lab the entire time you were there?

Later I worked as a technical controller. When the trailers for active uranium arrived, but the content wasn't high, I was supposed to go and check it. I did it really simply saying, "Guys, you are just fighting against yourselves. If you threw the big stones that don't contain any uranium away, but on the smaller ones that are obviously rich with the ore you put a paper "A" meaning they should be sent for the "active trailer" you have a much bigger chance to earn more money. If there is no uranium ore on your delivery they will dump it out, but if there is some, you will get 50 crowns per kilogram!" So they simply started doing this. (Laughing) One day a friend who had emigrated appeared. We grew up together. I asked him, "What are you doing here?" He replied, "Well I came back. Where do you work?" He showed me his identification and it said that he worked in the mine of Ludvík Svoboda[6] in Ostrava, but under a fake name. I told him, "Hey, play this game with someone else." So he told me what he was doing there and he slept over two or three times. In Jáchymov they created a forbidden zone and everyone who lived in Jáchymov had to have this information in their ID. This friend of mine was locked up in our village. He was arrested because he wanted to see his mother. He stayed at the place of an old woman who used to be a countess. Her property had been confiscated. They let her stay and live in a monastery. I imagine that she died in the monastery that night. Since her lights were on the men who were coming home from the pub, they were curious to see what she was doing. They threw a couple small stones in and because there was no reaction they went in. They wanted to ransack the house, but a policeman arrived at that moment. My friend was locked in another room there and couldn't escape because there were bars on the window. Anyway, he had a letter for me just with the message that he would go to Mariánské Lázně near Karlovy Vary and he would like to meet me. He was asking me if I could come to the train station. All in all, this letter was quite innocent. Now I am guessing because I never saw it. Then I was followed for about a month. My friend was locked up in March and I was locked up one month later.

What was your arrest like?

I was arrested on April 25, 1952. They certainly had been keeping their eyes on me. I had been transferred from Slavkov to Rovnost. They put me there probably so they could watch me because of the two collaborators they had. At the end of the afternoon shift that day I came out of the shaft. We came to the gate and they couldn't find my ID. The gatekeeper told me, "Come in." So I went in and then someone put their fingers into my back saying, "In the name of the Czechoslovakian Republic keep your arms at your side. You are being arrested." Then they dragged me outside and in front of the gate there was a Tatra police car with policemen standing next to it. A whole convoy of cars started moving and they took me down to Jáchymov to a place called Lužice, which was a spa house. There they put me into a cell, which already had four people. There was something like a bed made from wooden boards and on that was straw and a blanket. There we vegetated. There were two East Germans from Johanngeorgenstadt and two Czech boys and myself. There I stayed for 21 days. They took my pictures from both the front and side and they started investigating and interrogating. They knew about my friend and I couldn't deny that. I said, "He was here once on the day of miners. He came to see me from Ostrava and over there he worked in a mine of Ludvík Svoboda. He showed me his ID and ever since I haven't seen him." I imagine he said the same thing! We could not see each other in order to make this deal in advance. We were just lucky. Then they took me to Klatovy to the investigation department that they called Jestřáb (falcon). This was Jáchymov's counter espionage unit. Here they took anyone who either had tried to escape or was planning an escape. All these people were transported here and investigated. When I was locked up I was 92 kilograms (200 pounds). I knew this because the week before I had had a check-up. Three months later I was 61 kilograms (135 pounds). What a diet!

What were the conditions like in Klatovy?

In the morning and at noon we would get a small piece of bread, maybe 12 dekagrams (0,3 pound) and a little bit of black coffee, which we called mud. For lunch we got soup in a small enamel cup. Mine was numbered 49 sometimes 47. You know, in prison you try not to go crazy and you need to work and you need your mind to work somehow so for example I would count the knots in the wooden boards and I tried to remember how many did the third or fifth board have. I always counted 19 1/2 to 20 spoons of soup. That was lunch and sometimes for supper we would have the mud again. Only on Fridays did we get three small tiny unpeeled potatoes and coffee.

What was the hygiene like in Klatovy?

Hygiene...Well there wasn't any combs or any toothbrushes. There was a rag for washing the floor, 30x30cm (14x14 inches). We washed ourselves first with this rag and then we washed the floor. In Klatovy they gave us a bucket with water, which was also used for the floor afterwards. Plus, they would give us the cloth for the floor. , So first we would wash ourselves, then pour the water out and wipe off the floor. That was what the hygiene consisted of over there.

Did you stay in Klatovy the whole time?

No. They eventually took me to Nitra to meet my accuser. In Klatovy they handcuffed me and and kept me in a dark cell until they took me to see the officer. He was a sharp man. I refused to eat because I was being held in darkness. I kept asking myself, "Why am I being kept in the dark?" The officer called me out and demanded to know why I wouldn’t eat. I just replied, "Because I am here, I am in the dark, and nothing is happening." He sent me back, but not into the dark anymore. They put me into the cell next to the old one. There were two other prisoners there, Doctor Homola and an accountant from a cooperative. After five weeks they transported me to Nitra. One guard who was trying to be diligent took him to my cell. We were together for the whole night so we were able to explain things to one another.

Did you find out everything that your friend did and who was he working for?

He worked for the French. They were recruiting people among immigrants and he was supposed to go to the French Foreign Legion or to work in a company. His father was also in America, but it was his stepfather and he never invited him. My friend was hoping he would, but he never did. So he stayed in Germany and he worked for the French. He was coming to Czechoslovakia and he always went back. In Slovakia they finally caught him. He had a trial with another group of people in Slovakia because he formed two or three different groups, all together numbering fifty people. I was sentenced alone and transported from Nitra to Bratislava. On that day there was some really hot weather and they put me into a Škoda car and made me lie down. They put some fur coats that guards wore in winter over me. When they took me out of the car I was so sweaty that you can't imagine it. They took me up a stairs on a spiral staircase and up there I was put into a cell. I was completely exhausted and my head was buzzing and I lied down. A guard opened the door for food and asked, "What's wrong with you? Aren't you feeling well?" I didn't answer. He opened the door completely, came to me and asked, "Would you like to take a shower?" I said, "No, not really." "Are you sure?" "Yes." "Come and have a shower." He blindfolded me and we went up the steps. Once there they spun me around.

I didn't want to believe this was happening because I didn't have a good experience at Klatovy. There it happened that a guard came to me and asked if I wanted to take a bath. After he walked me there I didn't want to believe it. It was a beautiful clean warm bathtub. It was joy. I took my clothes off and everything started moving. Electricity! I fell out of the bath and the guard was just laughing. He was looking at me through the observation hole in the door laughing, "So what? Did you have a bath already?" I didn't even wipe myself off. I got dressed and he blindfolded me. He sent me walking blindly across the corridor and yelled, "Hey, I'm sending him to you." I bumped into something and it made a terrible commotion. I stepped on something and I fell over. There were washbasins and buckets stored there. I bumped into it, knocked it down on the concrete and in a second someone came up next to me and dragged me away. I never wanted to have a bath again.

Anyway in Bratislava I told myself that this guard looked nice so I went to take a shower, "Set the water as you like it," he said. I set the water, he gave me soap and a brush saying, "Take it easy and shower. Wash yourself properly." So I washed and I wiped myself off. I came back to the cell and he said, "Lay down. I'm guarding until taps so you can sleep." He asked me if I was hungry and I said yes. He brought me coffee, but it was sweet coffee for soldiers and a piece of bread. I ate it all and I fell asleep in a second. Do you know how I felt?! In the morning I woke up. He was there again and told me, "You are leaving today. I'm transporting you to Bohemia," and I went back to Klatovy.

You returned to Klatovy again from where you had such a bad experiences. Had anything changed there?

The food had changed beyond recognition. There was lunch. The food was served through a small little door and they would push your cup with soup towards you using their leg. We got one cup, a second cup and then the guy took it away. All of a sudden I saw something like a can and I just asked, "What is it?" We had eated the soup and all of a sudden there was another meal, some potatoes, some sauce, and a piece of meat. So I said, "Excuse me, but am I in Klatovy?" My prison mate answered, "Yes, that's the place." I responded, "This food?" "Well friend, we've had this food for about two weeks." So I asked, "Why?" There was a new prisoner who was a member of the International Red Cross who had been invited into the country because he was an expert on snake farms. He was imprisoned because an officer from the secret police who was a spy in Switzerland had been caught. It was understandable that they wanted to make an exchange so this specialist from the Red Cross was arrested so an exchange could happen. He refused to speak or eat. Two days later a consul came from Switzerland and threatened an inspection from the International Red Cross. They didn't do the inspection, but the food got better. We got a meal for lunch and supper which improved things a little bit.

I also have another story to tell you. In the cell there was an inmate named Pepík Fořt. Once he was called out and a little while later I heard a terrible cry and yelling underneath the windows. Soon after they brought Fořt back and put him back into his cell without his towel. The guy was white as a sheet. I asked him, "What’s wrong?" He was shakingand telling me, "Man, it was horrible. Do you know what happened? They took me and another prisoner and they let the dogs out to chase us, but the dogs went after the guards instead." Meanwhile we heard from our cell, "Serves you right then. You weren't supposed to do this. Why did you irritate the dogs wearing the Mukls’ clothing[7]? You thought they would go after the uniform, but they go after the smell." This guard was training the dogs to chase Mukls and he would do it dressed in a Mukl's uniform. He was quite brutal to the dogs in the cage. When they saw him coming they would growl. He thought they did this because of the uniform, but the dogs learned by sounds and smells. So in a moment after they took the two prisoners out and he stood by them, the dogs had pulled him down to the ground. Pepík Fořt quickly removed the blindfold from his eyes and saw one dog holding the guard's leg and the other his shoulder and they couldn't get them off. So Pepík was returned to his cell. Things like that happened there.

Could you describe in detail how the investigations went?

It went like this. They would take me there and in the beginning it was quite common interrogation, sweet things and reasoning that I had a family, a son, and that I would stay in prison for a long time if I did not cooperate. My son was born in December 1950. Once there came a lady who brought in some papers. She hit me so hard that I fell down off my chair. It was like a punch from a cannon shot. My teeth were broken and so I spit them out. They let me be like that. I refused to give testimony they wanted and so I wasn't allowed to sit. I had to keep walking in my cell and if I stopped for a second they would bang on the door. At night they kept waking me up even though I wasn't at any hearings or interrogations. Sometimes I would sit and five or six people in a circle would exchange seats at the table. One would ask you these questions and another would give you different ones to completely confuse you. I was practically sleeping, but I was still speaking and suddenly finding out that I didn't know what I was saying. These things were quite unpleasant. I had to keep marching. My legs were swollen from the sandals I wore. It was like standing on needles. My soles were swollen and I complained about it. They kept making up things about me all the time. At night they would kick my door, I would have to jump up, and report my presence every quarter of an hour. The light would be constantly on and we had to lay straight on our back with arms at the top of the cover. In a moment when I turned around there would be knocking at the door again. You had to jump up and report your presence once again. The arms had to be out because sometimes people would cut their wrists. We had to lie on our backs, the bulb was lit above our heads, but people still fell asleep because of the exhaustion.

Once I was ordered by an investigator to stand up by the wall. At that time there was paper money and I had to keep my arms behind my back holding the paper bill by my nose on the wall. The paper money fell down and I got such a slap from the back that my nose broke against the wall. They were laughing about it. Sometimes they would make me sit in the corner and threaten me with a saber, but the worst types of torture were the psychological ones. He would start by telling me that they will arrest my wife or say that she has already been arrested and that the kid has been taken away somewhere. They would ask, "What do you think you can do to us? We will make corpses out of you, your wives will become whores, and your children will become orphans We will bring them up and they will never even come to visit your grave."

What confession did they want to hear? What exactly was their goal?

They wanted to hear what I told my friend. I said, "From me he didn't want to hear anything." When I told him, he wouldn't get anything out of me and they said that they had information from other places. I was in Klatovy for two weeks maybe three weeks and then they put me in a car again and took me to Pankrác[8]. In the morning they woke me up, I had to take my clothes off, cross the cell to another side, take one step to the back, and lean against the wall. It got dusty down there and I had dustup to my armpits. They were spraying us with DDT. It was like an enema. It stunk and it burned. I came back to the cell and there was a guy waiting for me. When I came he said, "Hey, I will be washing you down." So I had to wash in the toilet. In Pánkrac we washed our dishes in the toilet and drank water from the toilet because there was nowhere else. There I stayed for about five weeks, I really don't know how long. Then they took us in an "Anton"[9] to Cheb. They took eight or nine of us.

So did you confess to anything?

No, there was nothing I could confess to. There was a trial and of course my defense attorney did a great job. He spoke to the court and the court as acknowledged that he was a court appointed lawyer. The court also said that it would not view the defense with sympathy because it's their duty not to and that it would be strict, but “fair” to my age. That was it. The prosecuting attorney made me out to be a real bad man such as a drunkard and an irresponsible person. I was also psychologically warped because I was raised in a monastery.

When were you sentenced?

I had my trial in October 1952. I got 18 of so-called hard labor. My civil liberties were stripped away for 10 years and all my property was confiscated. The National Senate in Cheb ruled that in my position I could divulge sensitive information about the country's defenses which is why they sentenced me to 18 years of hard labor. They had also suggested the death penalty, so I could be happy that I only got 18 years. I didn't believe though that the regime would last in this country for another forty years. I gave it five years, a maximum of six years.

What were you exactly charged for?

When they were handing out the sentence, I don't know how many pages there were in the charge. In the end there was a suggestion for capital punishment. Three days before the trial the head of the Senate read it to me. The next day another man came in telling me that he was now my court appointed attorney. He introduced himself as Dominic Skutecký or something like that. He told me that I should confess everything or I’d get the death penalty.

Where did they take you after the trial?

I was transported to the central camp in Jáchymov that was called Bratrství (Brotherhood). There they shaved our heads, changed our clothes, and received a couple new things. There were two blankets, a cup, a spoon, and clothes called "Halina." We were sorted into groups. I was sent to a place called Vršek and then they took me to Nikolaj. After two years I was taken from Nikolaj and sent back to Rovnost (Equality). In total I was interned for eight years. I was pardoned in 1960.

What were the relations like in camp? Did you have any friends there?

I had friends. When I came there were two other guys who came to see me from Slavkov. I knew they worked at Mine 11 and I helped them a couple of times because I used to work at Slavkov as a mine inspector. They brought me sugar and tobacco for which they could have gone to prison.

What was it like when you used to work there as a civilian employee and all of a sudden you were in the same position as a Mukl?

Well there was nothing I could do anything about it. . I was stuck there. It was helpless. Whenever civil workers who recognized me, started to approach me, I just told them, "Hey, keep back, continue in your work and don't pay any attention to me." I was worried that they would keep watching me and other peoples’ lives could be ruined and made miserable because of me. My wife lived in Jáchymov, but I never sent anyone to see her because I couldn't put her or the other person in danger as well even though she was under surveillance, which I'm sure of that. A couple of times when she came we were riding in the “Russian Bus.” Do you know what that is?

No. Could you be more specific?

Two hundred and fifty people had to stand up together according to the number that was supposed to go on the shift. They counted us on the square and then we had to come together so that we would be touching each other's’ hips and bodies. Then they went around us with a steel rope, which was about 5 millimeters thick and locked this with a padlock. In this way the whole package of people marched. I don't know if you can call it marching. We were actually jogging because the Eduard shaft was 800-900 meters away from camp Nikolaj. We had to go on the main road without a walkway or guard rail. It sometimes took us an hour to get there before we started jogging there...

What were the conditions like in Camp Nikolaj?

Camp Nikolaj had a reputation for being one of the worst camps. The main commander there was Šambergr. There was also a prisoners’ brigade, which made prisoners sentenced by the National Court sign the Socialist Commitment[10]. These prisoners were not called "political prisoners," but rather "state prisoners." One would commit himself to fulfill work quotas over 100 percent. If you didn't sign it, someone in the prisoners’ brigade would beat you up.

Did you know who was in that prisoners’ brigade?

Well the boss of the brigade was called Jeníček[11]. The whole group consisted of12 people if I remember it well. There were also guys such as Baxa, Kužela, Jirka or Gygar. The last thing they did was beat Honza Mátl and Sošenko. I don't remember who ran up to the building and told us, but we simply said we would not stand for it. So we all ran to the gatehouse and they started jumping out from the windows because they were scarred. They were always summoning people to the gatehouse to be beaten up. This time the brigade got a great whipping. They took all of them to the infirmary and Jeníček was transported to camp "L."[12]

When I say prison university, can you tell me anything about it?

Well yes, there were two things. First the guards gave us indoctrinations. There was a guy we nicknamed, "Filth." He was a cultural educator[13], and he would wake us up at 11pm and summon us to the culture house. All shifts had to go there and he would lecture us for an hour. He would always say, "Filth, is it right?" Those who were sitting in the first row would have to nod their heads. "Is that right, Filth?" That's why we called him "Filth." Once he gave a lecture called "Stalin Sent a Word." This meant he told us for one hour what was Stalin's message. Also there was another guy, another cultural educator we called "The One Who Told Seven Lies." This one was always saying, "What I'm telling you here are facts that really happened." At that moment no one could laughor he would explain to us the difference between socialism and capitalism. He would tell us to look how long it took the Soviet Union to dig a channel from the Volga to the Don. That was the work of the socialist camp. He would thentell us to look at how long it took the capitalists to dig the English Channel. You couldn't laugh about that.

Someone suggested that we should gather in the buildings. When you asked the guards politelythey would say yes. There was always someone giving a lecture on something. For example there were Baťovci[14] who told us about Baťa, his system, and so on. There were also professors who would give lectures about philosophy or chemistry. It depended on what you wanted to hear. So this was called the University of Jáchymov. Actually it was a good school for us you know. You could meet a lot of good people and learn wonderful things.

Do you have any health problems from prison?

I don’t see any major health consequences, but for example my fingers are cracking. I have these tiny little cracks. I got that from sorting the uranium. I worked four years at a place where uranium was sorted by hand. We didn't get any gloves. For a long time I had azoneurosis (not enough blood into his fingertips). Until this day, whenever the weather turns cold my fingers turn white. That comes from working with a machine, but all in all I don't have any other problem.

If we look at your story through the eyes of your wife, how did she handle this separation? You were a father of a family correct?

I think that our wives, parents, and families were psychologically affected much more because at least those of us in the prison were together. We all had similar attitudes. We were all of the same blood group, you could say. But those who stayed at home had it hard. People were turning their back on them, being malicious, and intentionally treating them badly. For example, the police would visit my wife at midnight with dogs, wake her up, trash the whole apartment, tell her that I had escaped. They would tell her that if I showed up she would have to report it or she would go to prison and that our kid would be sent away to a foster home. Then two weeks later they would tell her that they had caught me! They told the same stuff to my mom and in two weeks later they would tell her that I had been shot and wounded while trying to escape. At that time my mom had just received a permit for a visit. So she came and coincidentally at the time I happened to be injured. Some stones had fallen on me and had cut my eyebrow. I was also a little pale. My mom said, "Boy, why are you doing this? Don't you know that you have a family?" I didn't know what she was talking about. "Well, they will kill you." Then the guard jumped up and I replied, "Kill me?" Mom asked me where I had been shot and I pulled up my shirt asking, "Where was I shot?" The guard ended the visit telling us that we could only talk about family matters. I told him it was a family matter if they my mom that her son was shot, wounded, and constantly tries to escape! So they were harassing them as much as they could. They were pushing the women to divorce. They were switching them from one job to another, telling them if they divorce their husbands they will get better jobs.

While you were in prison, you made small gifts that you sent to your wife. Is that right?

I sent those not only to my wife, but to all my friends. You know we made them because we wanted to give something to our visitors. If you had a contact through a civilian worker there you could also send some things. For example, at Christmas time we made little cards, little figures, crosses, and other small gifts.

How was your return to civilian life like?

I felt really insecure. It took me a long time before I felt civilized again. I did a good thing by taking a month off after my release. I was supposed to report to the labor office, but I went to Slovakia instead. I told myself that I hadn’t had a vacation for eight years so why couldn't I have a rest? I let the doctors give me a proper check-up and they sent me back. They told me to get back into shape or it would be bad for me.

Why were they telling you this?

Well, it was because of the radioactivity exposure. I had about 14,000 white blood cells. Míla Adámek, who was a doctor prisoner studying the effects of radioactivity on people's health and was the biggest icon in this medical field, gave me two to three years to live if I left the mines. When we met in 1989 and I told him, "Miloš, hey you don't know how to count.” He said, “What do you mean?” And I said that you gave me two to three years to live. He just replied, "Be happy that I cannot count well..."

Where did you go when you came back from prison? What kind of job were you searching for?

I went back to Levice. There was an old onyx quarry there. They made various things out of it: paper weights, tables, various chess figurines, and other things made from stone. They wanted me to be a teacher at a trade school to teach penmanship. The doctors recommended that I get away from the radioactivity for a while and slowly let it work its way out, so I listened to them. They won’t let me go down into the shafts anymore because I was seriously ill. But I kept bravely going down until May when I was released.

What do you think about Charter 77, dissidents, and the year 1989[15]?

Well in my opinion they really didn't really want communism to disappear. They wanted communists to deliver on the promises they made in Helsinki. Why didn't they make dissidents out of us? Why did they execute and make criminals out of us? They executed 240 people. They beat to death many of them. Many of them died in mines and many on the borders. No one knows exactly today. There are many people who were reported missing, but somewhere their bones lie, and these people were truly dissidents. They once brought Goldstücker[16], Hromádka and Láďa - the guy who was a member of the Central Committee to Rovnost. Goldstücker was beaten at Rovnost really bad. They beat him like a horse. Do you know why? Because he made a statement in the United Nations that we did not have barbed wires in Czechoslovakia.

How do you as a political prisoner look at modern history? What would be the easiest way to tell this to the younger generation to inform them?

Tell them the truth. It's necessary to speak about these things. Freedom doesn't mean I can do anything I want. Freedom means responsibility so the things wouldn't fall apart. It means toleration. I don't care who is communist today. That ishis own business as long as he doesn’t do any harm to others. Or if someone is very religious. His faith is his own business and he can be in a political party that he likes. I imagine that in this government we have the positions for a reason so no to harm the nation. The opposition and the ruling coalition must agree on things that would benefit the whole country. The Germans were able to de-Nazify their offices. Why weren't we able to do it here?

What comes to mind when I say Jáchymov?

Jáchymov. One would rather forget about bad things. You can’t forget it, but you can stop thinking about it. It is like if someone does something bad to you, you forgive, but you do not forget. That's how I feel about Jáchymov. When you say “Jáchymov” the labor camps don't instantly come to mind. When people speak about them, I can recall everything like now. But they don't immediately come into my head.

After you were released, did you ever meet any of your guards, court prosecutors, or someone who influenced your life's destiny for such a while?

Yes, I met them. For example, when I applied for rehabilitation in 1969the lady prosecutor took a look at it and said, "Well yeah, that's clear." She gave me my charge and asked me whether I had read it and I said I didn't. So she asked why did you sign it? I just said I had to. If I didn’t it would have been bad for me. So everything looked in order. I was summoned to attend one of the last court hearings. I went to the regional court in Plzeň and the sitting judge was the same judge who had sentenced me. He was now chairman of the committee that was supposed to rehabilitate me. So I told myself, "That's it." He called me to the coffee table and asked me, "Do you know what happened in Chile?" I said, "Sure, there was a plot. Pinochet started a revolution." Then he said, "You see, then you cannot be rehabilitated." So because Pinochet started a rebellion in Chile, they could not rehabilitate me. So I asked, "What does Chile have to do with it?" He answered, "Well because we are all in the same camp." So I wasn't rehabilitated then. I was finally rehabilitated after 1989. I submitted another application and in a week I had a statement that I had been rehabilitated.

What do you think about the moral rehabilitation? Do political prisoners get enough attention?

You know I don't support the glorification of anyone. I only think the biggest satisfaction would come if the Bolsheviks would say they were sorry. If the political prisoners have accused someone, the process should be carried out to its logical conclusion. The person doesn't have to go to prison, since these people are also old. The nation should know what really happened. I'm not calling for anyone’s neck, but there were cases when people were executed under horrible circumstances. Even the surviving relatives of the executed never received any compensation. Money cannot make up for their loss. No one cares about these people today, although they live in deep poverty. Communists just laugh and ask whether someone should be compensated or they should be given back their property in which they stole from them in the first place. What kind of law is that? This is the time we live in and this is the law and we who are old can't do anything about it. It's a pity we are not twenty years younger.

Thank you very much for the interview.

[1] Slovak State (officially the Slovak Republic) Today´s Slovakia. It existed from1939 to 1945 and was truncated because of territory occupied by the Hungarians. The first Slovak Republic was a political and military ally of Nazi Germany.

[2] The Slovak National Rebellion - it was an armed uprising against the fascists in Slovakia near the end of WWII.

[3] Gulag was one of the departments of the secret police in the Socialistic bloc, managing a system of concentration and working camps in the U.S.S.R. The word gulag was then used for a group of these camps and camps under this institution.

[4] On March 14, 1939 the Slovak State was formed. This year was a national holiday from 1939 to 1945.

[5] The Communist Coup in February 1948 in former Czechoslovakia – see “history” section on our website.

[6] Ludvík Svoboda (1895 - 1979) was an army general. In 1945 he became Minister of Defense as an independent. In 1968 he was elected as president of Czechoslovakia.

[7] „Mukl" - someone who was in prison, the word "mukl" itself comes from the abbreviation of - "a man on death row" (in Czech: muž určený k likvidaci). It was a label given to political prisoners imprisoned by communist or Nazi regimes that were not supposed to be released and were supposed to die in prisons or concentration camps. Later on, this label was used for all political prisoners.

[8] Pankrác - a prison in Prague.

[9] "Anton" - a closed police van for transport of prisoners.

[10] Within socialistic commitments people promised for example to work extra hours or also on Sundays and national holidays. They then got various privileges, e.g. to write more letters home, to get more parcels. It was also promised they would be released earlier.

[11] Břetislav Jeníček was a leader among prisoners (the highest position in the prisoner´s autonomy). He was sentenced to life for cooperation with the Gestapo. In camp Nikolaj he made political prisoners´ lives tough, since he organized various brigades that beat prisoners.

[12] Camp called „L", sometimes called also a camp for liquidation. Here there was the so-called „”tower of death" where the prisoners came into direct contact with radioactive uranium.

[13] Cultural educator - Someone who organized various political and ideological lectures.

[14] Baťovci was name for a group of people who attended Baťa´s school. This school was established in Zlín by Tomáš Baťa who was one of the most successful businessmen during the First Czechoslovakian republic (1918-1938). He is an important icon in the history of management and business.

[15] Phenomena in modern Czechoslovakian history that are directly connected with the fall of the Communist regime in November 1989.

[16] Eduard Goldstücker – (1913 – 2000) Slovak of Jewish origin, professor of German literature, Czechoslovak Ambassador to Israel since 1948, imprisoned in 1951 from political reasons for 3,5 years, rehabilitated in 1955. Became a member of Czechoslovak Communist parliament in the 1960´, protested against Soviet occupation in 1968 and forced to leave to exile in the UK. Returned back to the democratic Czechoslovakia in 1990.