Selected remains of the camp

Former forced labour camp Nikolaj can be found about two kilometres north of upper Jáchymov. It lies 935 metres above sea level. Today, it’s on the yellow marked tourist trail that is shared with the Hell of Jáchymov Educational Trail. There is an informational panel on the side of the former driveway leading to the camp.

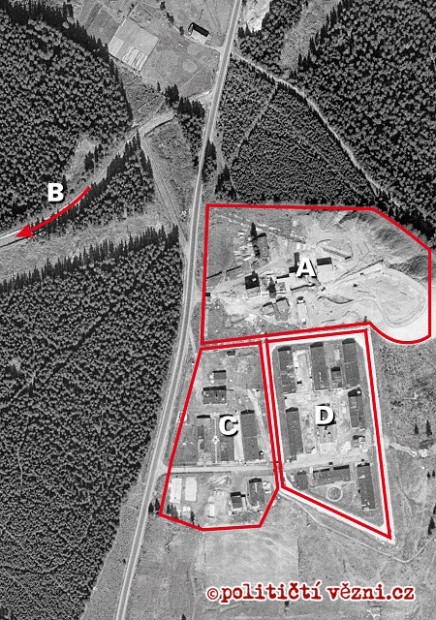

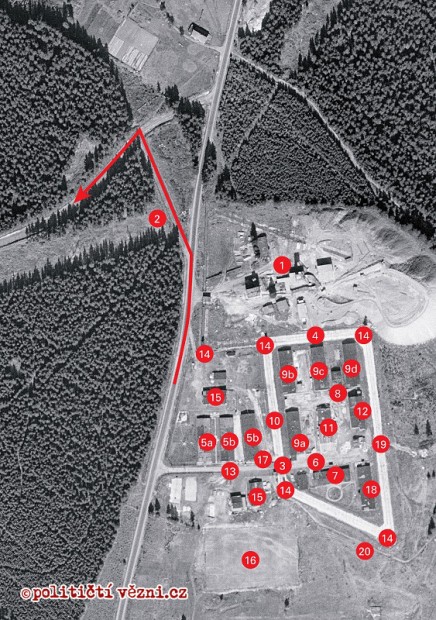

The remains of the Nikolaj labour camp can be divided into three parts. The first is the Nikolaj pit (A) where inmates worked back when Nikolaj was still a forced labour camp (TNP). After it was converted to a prisoner labour camp, mining efforts relocated to the nearby Eduard pit (B). The Nikolaj Camp itself was divided into a section for warders (C – housing, garages etc.) and the prisoner camp with facilities (D – housing, workshops, kitchen, culture house, solitary etc.). Both sections were secured to prevent escapes, but the prison part was guarded much more closely and included a free-fire zone with guard towers in the corners and barbed wire fences on both sides. Escaping the camp was extremely difficult.

“On the right, there was a slight slope that divided the camp into two unevenly sized parts. The larger part held the prisoner barracks, the kitchen, solitary, a drying room for mining clothes and the latrines; the smaller part contained several offices for the commanders, the culture house, the infirmary and the penal cell.” – Oldřich Klobas[1]

In 2017, we tried to gather all available information about the history and layout of the Nikolaj Camp and use it to identify traces found on the site. It’s not an easy task. There are few sources and few survivors. The only pictures we have are a handful of aerial photos (difficult to use because the layout of the camp changed over time) and so far, there hasn’t been any attempt to carry out an archaeological excavation. Despite that, we tried to identify everything as accurately as we could.

1) The Nikolaj Pit

The Nikolaj pit was located right next to the camp. At the beginning, when Nikolaj was a forced labour camp, this pit was worked by the inmates. After Nikolaj was converted to a prison camp, however, only civilian miners worked here. The pit was eventually closed completely; the mining equipment was disassembled and the entrance was sealed. Two of the original buildings are still standing; they are used as summer homes.

2) Road to the Eduard Pit

Prisoners from Nikolaj were mining uranium in the Eduard pit, located about a kilometre and a half away. Because there was a busy road connecting the camp and the pit, the prisoners couldn’t walk through a fenced corridor as in the other camps. For this reason, they marched down the road in a human cluster tied together with a steel wire rope; the prisoners called this the “Russian bus” (sometimes the “Jáchymov bus” or the “MUKL bus”).[2]

“It’s not difficult to make a MUKL bus, which was important, given the intellectual capacity of the warders. Once all the prisoners ready to march to the pit were counted, the head of the escort nodded to the brigadier. The brigadier shouted: ‘Grab!’ and groups of five had to stand as close as possible and grab the person in front of them around the waist. When they were all tightly packed together, the brigadier wrapped the entire group with steel wire at waist height and locked the wire in the back with a padlock. The key was then handed over to the head of the escort. When the order was given, the whole shift of two to four hundred people started marching. Everyone had to start at the same time and with the same foot, because otherwise chaos ensued. Trouble started when someone tripped and broke the rhythm. Before the bus could stop, this man fell to the ground and everyone walked over him.” – Oldřich Klobas.[3]

3) The Camp Gate

The main gate of Nikolaj Camp was located about 100 metres from the main road, connected by a gravel driveway. The gate was large, with a smaller side gate for individual people. Close to it were the warder barracks, the commander’s office and one of the guard towers. The gate was pulled down when the camp was disbanded.

4) Free-Fire Zone

The Nikolaj Camp was closely guarded and surrounded by a corridor of barbed wire obstacles. The most carefully watched central part was ringed by two fences, each three metres high; there was a strip of sand between the two fences that was regularly raked and weeded.[4] There were six guard towers in total, located in the corners.

“The camp is surrounded by a double barbed wire fence, at least three metres high. Between the two fences, there is a corridor about two metres wide, covered with meticulously raked white sand. In the corners, there are high watchtowers with guards armed with machine guns. Three metres from the fence, there is barbed wire marking the free-fire zone; there are signs informing prisoners that anyone in this zone may be shot without warning.” – Miroslav Šlechta[5]

The fences were torn down when the camp was disbanded, but the free-fire corridor is still visible in aerial photos if you look closely. At certain times of the year, it seems that there are different kinds of trees growing inside the camp than outside.

5) Warders’ Barracks

Three prefab wooden barracks along the entrance road served as housing for the commander (5a) and other personnel (5b). They were of the same size as the prisoners’ barracks. There was a wooden fence on the side towards the camp, preventing inmates from looking in. In the aerial photos, it seems that the yard in front of the commander’s building was somewhat cultivated. Only the foundations of the buildings are visible today.

“Paleček was a famous commander. Small in stature, but larger than life in his actions, always with a smile on his face. Whenever he went on one of his inspections of the camp, he held a bunch of keys in his fist. Everyone who hadn’t managed to hide somewhere froze in their tracks when he was passing by. They slammed their caps against their thighs, and in response Paleček nodded with a smile. Then, unexpectedly, suddenly, yet still in a good mood, he struck, opening his fist and pressing the keys into one of the prisoners’ faces, and with an unchanged expression continued towards his next randomly selected victim.” – Karel Pecka[6]

6) Appellplatz

The yard used for roll calls, generally known as the Appellplatz, was located just beyond the main gate, on a slight slope between the culture house and the kitchen. There were three roll calls every day during which the prisoners assembled and were counted, standing in one place for hours even in cruel winters. “During the morning roll call, they often let us stand in 32 degrees minus for an hour and a half while the warders played cards in the guardhouse.”[7] The Appellplatz was also the final stop of the “Russian bus” departing from the Eduard pit. During the tense period after political prisoners refused to accept their new performance objectives, roll calls became an opportunity for merciless bullying. In his memoir, Karel Pecka describes the violent “class struggle games” organised by the camp commanders which he ironically called “Passion Plays”.

„That was in Nikolaj. There were twelve hundred people there; a medium-sized camp. Early on, there were less than a hundred state prisoners among them. And an insane political educator who organised these class struggle games. On a Sunday when there wasn’t much to do, he’d place the one hundred political prisoners on one end of the camp, carrying signs reading ‘Death to communism!’ and stuff like that, and on the other end of the camp everyone else, representing the working class. He gave the order and they marched against each other. (…) There were eleven hundred against a hundred, clashing on the Appellplatz; the commander was watching it as if from a tribune, a spectator on the gallery, cheering for his team. Some thought it was a joke, but others took it very seriously. And so they bravely defeated the reactionaries; threw them to the ground and tore their placards to pieces. There was also a pile of rocks from the old pit, and in order to atone for their crimes, the beaten class enemies had to carry them to another pile. And then back again.” – Karel Pecka[8]

The violence lasted until August 1952. Paradoxically, one of the factors that helped end this period were complaints of the Soviet advisers who didn’t like the poor work performance of the bullied political prisoners.

The Nikolaj Appellplatz can still be recognised by the nearby remains of the culture house.

7) Culture House

The culture house was used for regular political lectures, meetings of the camp self-administration and various cultural events (film screenings and concerts of the camp orchestra). The building also housed offices of the camp commanders. Occasionally, the culture house was also used as makeshift barracks. After the relative improvement of conditions in the camp following Stalin’s death, a meeting in the culture house elected a self-government of political prisoners. According to survivors, however, the camp commanders did not tolerate its existence for long.

“This soon turned into attempts to create a system of prisoner self-administration. Until then, the only thing resembling self-administration were the punitive commandos who went around the barracks at nights and beat people up, as I mentioned. But then a new political educator was assigned to Nikolaj, and naïve as he was, he took this completely seriously. There even was an election, which I believe was the first free election behind the Iron Curtain since 1948 – and right in Nikolaj, one of the worst labour camps. (…) In the election, none of the political educator’s lackeys got through, but the prisoners picked their self-government from those whom they trusted. This was sometime in August 1953. On 9 September, it was Miners’ Day, which was a day off. (…) In the morning, they called in everyone from the self-administration, and we went, thinking it was a meeting – and instead they marched us to solitary confinement as hostages. To keep the peace in the camp, they said.” – Karel Pecka[9]

On some of the aerial photos, there is a footworn circular path behind the culture house. According to survivors, at one point the prisoners planted flowers there. The site of the culture house can still be identified by a concrete kerb that ran along its front side. The place where it stood is now home to several spruce trees.

8) Solitary Confinement

Between autumn and winter of 1955, a brick structure was built on this site. Solitary confinement, often called “correction”, was a prison within a prison; inmates were locked in here for various transgressions, even though the real reason was often simple bullying. The old solitary confinement building was probably located in a different part of the camp.

“That’s when I found myself in the brand new correction, a small building without a cellar which had about five cells on either side. The floor was xylolite and the walls completely smooth; there was a bucket, reinforced glass in the window covered by sheet metal from the outside and a light above the entrance, well beyond reach – and that was it, in a room of about three by two metres. The only other things in it were humidity and cold, which was the biggest problem. Water was condensing in droplets on the walls, forming puddles on the floor. Everything gave out the raw smell of a new building. I spent the day walking around the cell; they took away our outer clothes, so I was there just in my underwear and boots without laces, so I needed to warm up somehow.” – Karel Pecka[10]

9) Prisoner Barracks

Prisoners in Nikolaj lived in four standardised wooden buildings standing on brick pillars. “Like in any other prison camp, there were rows of long wooden houses. There was a long corridor running down the middle and on both sides rooms with bunk beds for 20 to 30 people.”[11] The buildings were marked 1–4 or A–D. Numerous cracks in the floor let in cold air and during winter even snow. After 1954, washrooms and toilets were built in the back of each building.[12] The first of the barracks was located right next to the camp gate, opposite the culture house. On the side facing the gate, there was an extension which served as the guardhouse[13] and on the other side a carpentry workshop. There was a volleyball court between barracks 2 and 3.

Survivor memoirs describe one specific event linked to building number one: an organised attack on the political prisoners living inside. On Labour Day 1952, the head of the camp’s “beating commando” Břetislav Jeníček gathered his men in the culture house and opened a meeting: “I explained to the camp who reactionaries were, urged the camp to be loyal to our people’s democracy, and gave examples of certain types of reactionaries who avoid work. (…) Then I asked the convicts to march through the camp with signs that we’d made earlier. (…) Then they were dismissed; suddenly someone ran in saying that a reactionary had been beaten up in barrack one. So the whole camp started shouting slogans against the reactionaries and about a hundred men forced their way into the first building and a brawl broke out. We threw them out of the windows, threw out their things and beat them up in the corridors.”[14]

There’s another recorded memory concerning building number four, located in the most remote part of the camp. Here the Catholic activist and political prisoner Václav Vaško experienced his first prison mass. “The camp elder assigned me to building four which was in the back of the camp and to the left. I was to stay in the last but one room on the left-hand side. (…) The “general vicar” of the camp was Augustin Krajčík, a Slovak Redemptorist. I timidly walked into his room. “Václav, is that you?” I was greeted heartily by my friend from Bratislava, a member of Kolakovič’s “Family” Gažo Fronc. We hugged. I was just in time for mass. He introduced me to Father Krajčík and the mass started; my first in prison. Our chapel was the aisle between the beds. Our altar a straw mattress on the upper bunk. The chalice was a discarded ampoule, the paten a clean handkerchief and the wine and the host were smuggled to us by one of the civilian miners. The priest was standing, Gažo acted as the altar server, someone stood in the back of the aisle and three men from east Slovakia and I were sitting on the bottom bunk.”[15]

The barracks were demolished after the camp had been disbanded. Our search on the site of building number one uncovered overgrown remains of the columns on which the wooden construction once stood. It can be assumed that there are similar remains to be found on the sites of the other buildings as well. Sewer holes located near the buildings also remain visible to this day.

10) Tunnel

In 1955, the rear part of the first building was converted to a small carpentry workshop, and here a group of political prisoners dug a tunnel about twenty metres long. The tunnel led under the free-fire zone into a shallow ditch near the warders’ barracks. On Sunday 6 November 1955, the comedy film Cirkus bude was shown in the culture house to a packed audience. Ten political prisoners took advantage of the commotion and escaped through the tunnel. Even though they had several hours of head start, they were all eventually caught. One of the escapees was Anton Tomík who joined us on one of our inspections of the camp. The entrance to the tunnel was hidden under a closet. The dug-out earth was secretly stored on the building’s roof. Timbering in the tunnel was improvised with bits of broken tables, chairs etc.[16] This was the only successful tunnel escape in the entire Jáchymov region.

11) Kitchen

In the centre of the main part of the camp was the kitchen combined with a dining area, canteen and a library in the back. The original standardised wooden construction was probably extended and its front part rebuilt in 1956. According to Karel Pecka, the underground storage area of the kitchen was at some point temporarily used as correction. “In Nikolaj, during one of the worst but not critical periods, they brought in a transport of Jehovah’s Witnesses, a sect that refuses to use weapons. That was what they were sentenced for: they were willing to tend the sick, but not to hold a gun in their hands. Which was obviously a dreadful crime, so they each got ten to fifteen years. And then they were brought in and were supposed to go mine uranium! They did assemble for the roll call, but then, understandably, refused to go. The whole group of about twenty people was then put in correction, which was a bit funny, because that was before they built the new one, so it was really just a cellar separated by a wooden partition from the potato storehouse. They were sitting there and singing their songs that could be heard outside. (…) Thanks to the raw potatoes, they didn’t die immediately, but as we walked by day after day, the singing grew weaker and weaker. After some ten or twelve days, it was only very faint and one day, we returned from our shift and it was all quiet. Then a truck came in, they threw them inside, most of them unconscious, and took them away.” – Karel Pecka[17]

There are several traces remaining of the kitchen, including the foundations and an underground area which features small rooms with barred windows. According to Miroslav Kopta, there was a cellar under the kitchen where the prisoners stored potatoes; this might be the part that survives to this day.

12) Drying Room and Warehouse

Roughly in 1953, a drying room for mining clothes was built here which also contained a washroom and a warehouse for mining equipment. Before then, prisoners used to hang their clothes in the corridors of the barracks to dry.[18] The camp barber also worked here. According to some sources, this building was known as “E” (or “éčko”).

13) Driveway

The driveway connected the camp gate to the main road. The driveway survives intact and now serves as the main access road to the remains of the Nikolaj Camp.

14) Guard Tower

Guard towers were located in the corners of the free-fire zone around the camp’s most heavily guarded section. They were torn down after the camp had been disbanded.

15) Commander’s Offices

The camp commander had his office by the driveway, just before the camp gate. It was located opposite the warders’ barracks. Right next to it was a garage and, closer to the road, a car park.

16) Football Pitch

The football pitch was located between the commander’s offices and the main road: “To the right of the driveway was a football pitch where the commanders were showing off their skills. It was here that I did the worst job of my entire life. As political prisoners of the communist regime of Gottwald, Zápotocký and Novotný, twenty convicts and I had to remove half a metre of snow from the entire pitch, in heavy rain while an icy wind was blowing. We were dressed in our light shabby clothes, with no coats or gloves and in flimsy shoes. The head of the shift dropped by often to watch our progress. He didn’t care that we just came back after heavy work in the pit and that we were starving. He had thick clothes and his belly was quite full.” – Josef J. Staněk[19]

17) Guardhouse

The guardhouse, also referred to as the “gate”, was located at the entrance. It was built as an extension of the outermost of the warders’ barracks.

18) Infirmary and Penal Cell

According to survivors, this standardised wooden building was divided into two parts: a penal cell in the front and the infirmary in the back. The infirmary had a separate entrance on the side. The penal cell was used for example for prisoners who did not meet performance standards and were punished by smaller meals as well as demeaning tasks.

“I was injured twice in Nikolaj. One of those times was really bad. I was carrying some stuff from the worksite, a ladder snapped under me and I fell. It was about four metres down and I fell with my back first; I cut open my elbow and dislocated my shoulder. I climbed down to the headframe and told the workers there to tell Husník I was injured, and they took me up. I was treated at the infirmary; the doctor sewed me up. This was on a Friday; on Monday, I had to go back to work.” – Zdeněk Kovařík. [20]

19) Toilets

This part of the camp held the latrines as well as a rubbish dump. The waste from the latrines was led outside the camp under the free-fire zone. The camp latrines don’t feature very often in survivor stories. It is here that Svoboda, the main character of Karel Pecka’s novel Motáky nezvěstnému, removes a capsule containing camp poetry from his rectum.[21] A less known story features the camp commander’s dog: “One of the Nikolaj commanders had a fox terrier; he’d walk with it around the camp and the dog was bothering and sometimes attacking the inmates. Sometimes the dog ran around without his master. He shouldn’t have done that. He ended up with a broken back in the twelve-seat latrine. It was only discovered by accident when six months later his corpse plugged the pipe of the fecal sludge truck. That was pretty cruel. Both to the dog and to us. The whole camp lost all privileges for a month.[22]

After the camp had been disbanded, the building was torn down; a new forest grew in the vicinity and today hides what used to be a nice view. Miroslav Kopt mentioned that he often took “mediation walks” around the fence in this part of the camp, looking at the hilly landscape.

20) Footpath

There was a footpath leading from the camp gate to the Městský Lake. According to survivors, it was used by border patrol guards who had their headquarters in a house on the shore. The house is still standing and is today used as a private cottage.

[1] KLOBAS, Oldřich. Jak se chodí v laně: svědectví politického vězně z padesátých let o jáchymovském táboře Nikolaj. Telč: Dobrý důvod, 2008. p. 168.

[2] MUKL, a commonly used abbreviation, stands for “muž určený k likvidaci”, or “a man designated for liquidation”.

[3] KLOBAS, Oldřich. Jak se chodí v laně: svědectví politického vězně z padesátých let o jáchymovském táboře Nikolaj. Telč: Dobrý důvod, 2008. p. 170.

[4] ŠEDIVÝ, František. Legie živých, aneb, Jáchymovské peklo: [autobiografický příběh politického vězně]. Prague: EVA – Milan Nevole, 2008. p. 11.

[5] LOUČ, Michal. Rozhovor s Miroslavem Šlechtou. In: Političtí vězni.cz [online]. Prague: Spolek Političtí vězni.cz, 2017 [retrieved 2017-07-12]. Available at: http://www.politictivezni.cz/miroslav-slechta-pracovnici-ptp.html.

[6] PECKA, Karel. Motáky nezvěstnému. Brno: Atlantis, 1990. p. 226.

[7] [ZODPOVEDNY D. GREGOR]. Otvorené oči: spomienky politických väzňov. Čadca: OP KPVS ČADCA. p. 53.

[8] BARTOŠEK, Karel. Český vězeň: svědectví politických vězeňkyň a vězňů let padesátých, šedesátých a sedmdesátých. Prague: Paseka, 2001. p. 27.

[9] LUKEŠ, Jan and PECKA, Karel. Hry doopravdy: rozhovor se spisovatelem Karlem Peckou. Litomyšl: Paseka, 1998. p. 96.

[10] LUKEŠ, Jan and PECKA, Karel. Hry doopravdy: rozhovor se spisovatelem Karlem Peckou. Litomyšl: Paseka, 1998. p. 118.

[11] LOUČ, Michal. Rozhovor s Miroslavem Šlechtou. In: Političtí vězni.cz [online]. Prague: Spolek Političtí vězni.cz, 2017 [retrieved 2017-07-12]. Available at: http://www.politictivezni.cz/miroslav-slechta-pracovnici-ptp.html

[12] ŠEDIVÝ, František. Legie živých, aneb, Jáchymovské peklo: [autobiografický příběh politického vězně]. Prague: EVA – Milan Nevole, 2008. p. 12.

[13] “Right next to the gate, tacked on the front of barrack no. 1, was an extension which was the kingdom of the two heads of shift, Mikuláš Péchy known as Miky and Jarda Plotěný from Brno.” KLOBAS, Oldřich. Jak se chodí v laně: svědectví politického vězně z padesátých let o jáchymovském táboře Nikolaj. Telč: Dobrý důvod, 2008. p. 168.

[14] BAŠTA, Jan. “Boj proti reakci v NPT Nikolaj.” In: Securitas imperii: Sborník k problematice bezpečnostních služeb. Prague: Úřad dokumentace a vyšetřování zločinů komunismu, 2005, p. 283–284.

[15] VAŠKO, Václav. Moje první mše v komunistickém vězení. In: Pastorace.cz: Podklady pro pastoraci a duchovní život [online]. 2012 [retrieved on 2017-07-25]. Available at: http://www.pastorace.cz/Clanky/Moje-prvni-mse-ve-vezeni.html

[16] ROTTENBORN, Oldřich, and BOBEK, František. Skauti za mřížemi totality. Prague: Ostříž, 1993. p. 53.

[17] LUKEŠ, Jan and PECKA, Karel. Hry doopravdy: rozhovor se spisovatelem Karlem Peckou. Litomyšl: Paseka, 1998. p. 92.

[18] ŠEDIVÝ, František. Legie živých, aneb, Jáchymovské peklo: [autobiografický příběh politického vězně]. Prague: EVA – Milan Nevole, 2008. p. 72.

[19] STANĚK, Josef J. Potrestaní. Haarlem: Czechoslovak Cultural Club, 1976. p. 27.

[20] BOUŠKA, Tomáš. Rozhovor se Zdeňkem Kovaříkem. In: Političtí vězni.cz [online]. Prague: Spolek Političtí vězni.cz, 2017 [retrieved 2017-07-12]. Available at: http://www.politictivezni.cz/rozhovor-se-zdenkem-kovarikem.html

[21] PECKA, Karel. Motáky nezvěstnému. Brno: Atlantis, 1990. p. 289.

[22] SVĚTLÍK, Jiří. Paměti starého kriminálníka. Plzeň: Ing. Petr Mikota, 2015. p. 48.